>>510489429

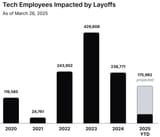

The social and political consequences will be profound. And the trend is not just in America. Across the European Union the unemployment rate of young folk with tertiary education is approaching the overall rate for that age group (see chart 1). Britain, Canada, Japan—all appear to be on a similar path. Even elite youngsters, such as MBA gradates, are suffering. In 2024, 80% of Stanford’s business-school graduates had a job three months after leaving, down from 91% in 2021. At first glance, the Stanford students eating al fresco at the school’s cafeteria look happy. Look again, and you can see the fear in their eyes.

Until recently the “university wage premium”, where graduates earn more than others, was growing (see chart 2). More recently, though, it has shrunk, including in America, Britain and Canada. Using data on young Americans from the New York branch of the Federal Reserve, we estimate that in 2015 the median college graduate earned 69% more than the median high-school graduate. By last year, the premium had shrunk to 50%.

Jobs are also less fulfilling. A large survey suggests America’s “graduate satisfaction gap”—how much more likely graduates are to say they are “very satisfied” with their job than non-graduates—is now around three percentage points, down from a long-run advantage of seven.

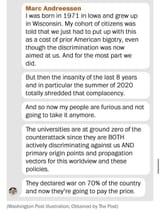

Is it a bad thing if graduates lose their privileges? Ethically, not really. No group has a right to outperform the average. But practically, it might be. History shows that when brainy people—or people who think they are brainy—do worse than they think they ought to, bad things happen.

7/16/2025, 12:45:28 AM

No.510488209

[Report]

>>510488776

>>510489243

>>510490653

>>510491088

>>510491494

>>510492162

>>510492442

>>510493596

>>510493671

>>510494426

>>510495285

>>510495402

>>510497025

>>510508066

>>510508335

>>510508517

>>510518243

>>510519274

7/16/2025, 12:45:28 AM

No.510488209

[Report]

>>510488776

>>510489243

>>510490653

>>510491088

>>510491494

>>510492162

>>510492442

>>510493596

>>510493671

>>510494426

>>510495285

>>510495402

>>510497025

>>510508066

>>510508335

>>510508517

>>510518243

>>510519274