Anonymous

ID: XyYkEbtD

8/19/2025, 8:38:04 AM No.513436738

https://archive.ph/yzz9y

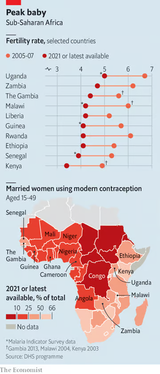

Africa’s birth rate is falling far more quickly than expected. Though plenty of growth is still baked in, this could have a huge impact on Africa’s total population by 2100. It could also provide a big boost to the continent’s economic development. “We have been underestimating what is happening in terms of fertility change in Africa,” says Jose Rimon II of Johns Hopkins University. “Africa will probably undergo the same kind of rapid changes as east Asia did.”

The UN’s population projections are widely seen as the most authoritative. Its latest report, published last year, contained considerably lower estimates for sub-Saharan Africa than those of a decade ago. For Nigeria, which has Africa’s biggest population numbering about 213m people, the UN has reduced its forecast for 2060 by more than 100m people (down to around 429m). By 2100 it expects the country to have about 550m people, more than 350m fewer than it reckoned a decade ago.

A similar trend seems to be emerging in parts of the Sahel, which still has some of Africa’s highest fertility rates, and coastal west Africa. In Mali, for instance, the fertility rate fell from 6.3 to a still high 5.7 in six years. Senegal’s, at 3.9 in 2021, equates to one fewer baby per woman than little over a decade ago. So too in the Gambia, where the rate plunged from 5.6 in 2013 to 4.4 in 2020, and Ghana, where it fell from 4.2 to 3.8 in just three years.

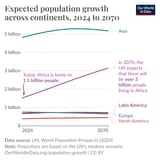

Others are also reducing their projections. In 1972 the Club of Rome, a think-tank, published an influential book, “The Limits to Growth”, warning that consumption and population growth would lead to economic collapse. Now it says the population bomb may never go off: it reckons sub-Saharan Africa’s population may peak as soon as 2060, which is 40 years earlier than the UN’s projections.

Africa’s birth rate is falling far more quickly than expected. Though plenty of growth is still baked in, this could have a huge impact on Africa’s total population by 2100. It could also provide a big boost to the continent’s economic development. “We have been underestimating what is happening in terms of fertility change in Africa,” says Jose Rimon II of Johns Hopkins University. “Africa will probably undergo the same kind of rapid changes as east Asia did.”

The UN’s population projections are widely seen as the most authoritative. Its latest report, published last year, contained considerably lower estimates for sub-Saharan Africa than those of a decade ago. For Nigeria, which has Africa’s biggest population numbering about 213m people, the UN has reduced its forecast for 2060 by more than 100m people (down to around 429m). By 2100 it expects the country to have about 550m people, more than 350m fewer than it reckoned a decade ago.

A similar trend seems to be emerging in parts of the Sahel, which still has some of Africa’s highest fertility rates, and coastal west Africa. In Mali, for instance, the fertility rate fell from 6.3 to a still high 5.7 in six years. Senegal’s, at 3.9 in 2021, equates to one fewer baby per woman than little over a decade ago. So too in the Gambia, where the rate plunged from 5.6 in 2013 to 4.4 in 2020, and Ghana, where it fell from 4.2 to 3.8 in just three years.

Others are also reducing their projections. In 1972 the Club of Rome, a think-tank, published an influential book, “The Limits to Growth”, warning that consumption and population growth would lead to economic collapse. Now it says the population bomb may never go off: it reckons sub-Saharan Africa’s population may peak as soon as 2060, which is 40 years earlier than the UN’s projections.

Replies: