Search Results

6/21/2025, 8:03:03 AM

>>17780354

The political context also reinforces this view. In the Battle of the Ten Kings (Dasarajna), recorded in the Rigveda, King Sudasa and his priest Vishvamitra (of the Kanva lineage) represent a group that worshipped Indra and Soma, as opposed to a coalition of ten rival Indo-Aryan tribes whose priests belonged to the lineages associated with Bharadvaja and Gautama, who placed greater emphasis on gods such as Varuṇa and Mitra and had divergent ritual practices. In the Rigveda itself, these names, Vishvamitra, Kanva, Bharadvaja, Gautama and other families, appear as Rishis and hymn-writers, each symbolizing one of the ten or so distinct lineages of the Vedic corpus, which claimed different mandalas: Kanva (Mandala 8), Vishvamitra (Mandala 7), Bharadvaja (Mandala 6) and Gautama (Mandala 10). The formal idea of a school crystallized later, but these families already indicated clear oral and authorial divisions.

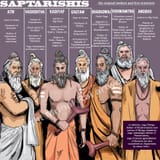

These Rishis are part of the group known as the Saptarshi and Brahmarshi, the seven sages who in the other Vedas, Upanishads, and later Puranic literature are considered mental sons of Prajapati/Brahma and fathers of Devas and other divine beings such as Kashyapa with the Adityas, Rudras, Vasus, Daityas, Maruts, Danavas, Nagas, Manasa, Iravati, Gandharvas, Aruna, Garuda, etc. Thus, they not only symbolize the rival priestly lineages, but also assume a divine role in mythology, as founders of the order and ancestors of the gods.

The differences between these families reflect theological and ritual tensions, the strong emphasis on Indra and Soma ritual by Visvamitra and Kaṇva versus the valorization of Varuṇa, Mitra, and the moral order by Bharadvāja and Gautama. The Battle of the Ten Kings symbolizes not only a political conflict, but a religious and cultural dispute, showing that the Indo-Aryans never had a unified tradition, but a field in constant dispute where myths and gods were reinterpreted according to local interests.

The political context also reinforces this view. In the Battle of the Ten Kings (Dasarajna), recorded in the Rigveda, King Sudasa and his priest Vishvamitra (of the Kanva lineage) represent a group that worshipped Indra and Soma, as opposed to a coalition of ten rival Indo-Aryan tribes whose priests belonged to the lineages associated with Bharadvaja and Gautama, who placed greater emphasis on gods such as Varuṇa and Mitra and had divergent ritual practices. In the Rigveda itself, these names, Vishvamitra, Kanva, Bharadvaja, Gautama and other families, appear as Rishis and hymn-writers, each symbolizing one of the ten or so distinct lineages of the Vedic corpus, which claimed different mandalas: Kanva (Mandala 8), Vishvamitra (Mandala 7), Bharadvaja (Mandala 6) and Gautama (Mandala 10). The formal idea of a school crystallized later, but these families already indicated clear oral and authorial divisions.

These Rishis are part of the group known as the Saptarshi and Brahmarshi, the seven sages who in the other Vedas, Upanishads, and later Puranic literature are considered mental sons of Prajapati/Brahma and fathers of Devas and other divine beings such as Kashyapa with the Adityas, Rudras, Vasus, Daityas, Maruts, Danavas, Nagas, Manasa, Iravati, Gandharvas, Aruna, Garuda, etc. Thus, they not only symbolize the rival priestly lineages, but also assume a divine role in mythology, as founders of the order and ancestors of the gods.

The differences between these families reflect theological and ritual tensions, the strong emphasis on Indra and Soma ritual by Visvamitra and Kaṇva versus the valorization of Varuṇa, Mitra, and the moral order by Bharadvāja and Gautama. The Battle of the Ten Kings symbolizes not only a political conflict, but a religious and cultural dispute, showing that the Indo-Aryans never had a unified tradition, but a field in constant dispute where myths and gods were reinterpreted according to local interests.

Page 1